Heidi Uhing, April 22, 2021

Nebraska research to celebrate on Earth Day

Earth Day, annually celebrated April 22, is a call to address climate change and protect lands, air, water and wildlife. Chancellor Ronnie Green has named climate resilience and sustainable food and water security as two grand challenges to focus the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s collaborative efforts on using its unique expertise to address. The following stories highlight recent research efforts that are bringing Nebraska and the world closer to understanding these challenges and protecting the environment.

Data collection project to help farmers address greenhouse gas emissions

Who: Christopher Neale, director of research, Robert B. Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute and professor of biological systems engineering; Timothy Arkebauer, professor of agronomy and horticulture; Andy Suyker, associate professor, School of Natural Resources; and Virginia Jin, U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research scientist

What: University of Nebraska–Lincoln researchers affiliated with the Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute received a $3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy to better quantify carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions connected with corn production fields in the Midwest.

The Nebraska-led group is one of six tapped by the agency to do careful greenhouse gas measurements in production fields for grain crops that supply the ethanol industry. Corn and soybeans are the project’s focus. The data gathered will help inform American farmers to improve their operations and participate in bioenergy and carbon markets expected to develop in coming years.

“Our objective is to measure all greenhouse gases being emitted and also being sequestered at fields in Nebraska, Iowa and Minnesota,” Neale said. “Our ultimate goal is to establish how much carbon credit a typical farmer creates, based on soil types, production systems, crops and so forth.”

Engineered microbe excels at ‘breathing rubber,’ could curb reliance on petroleum

Who: Nicole Buan, associate professor of biochemistry; Sean Carr, doctoral student, biological sciences; Karrie Weber, associate professor of Earth and atmospheric sciences and biological sciences; and Jared Aldridge, Nebraska alumnus

What: Single-celled microorganisms known as methanogens are known for emitting methane: in the guts of humans and other animals, in hydrothermal vents that gash the ocean floor — almost anywhere, really, that oxygen is not.

Biochemist Buan and her research team have now genetically engineered a species of methanogen that can also yield sizable amounts of isoprene, the primary chemical component of synthetic rubber. Promisingly, that isoprene production substantially outpaces the yields of other microorganisms engineered for the same purpose.

Roughly 800,000 tons of isoprene, most of which is used to produce synthetic rubber, are refined from petroleum annually. A climate-conscious desire to reduce reliance on the fossil fuel has pushed researchers to seek alternative, renewable sources of the chemical.

“[Methanogens] are really incredible, really magical organisms,” Buan said. “They can grow in a sealed glass vessel with just some minerals, and that’s it. To me, they had the highest potential for developing sustainable technologies that could really revolutionize our climate and energy needs.”

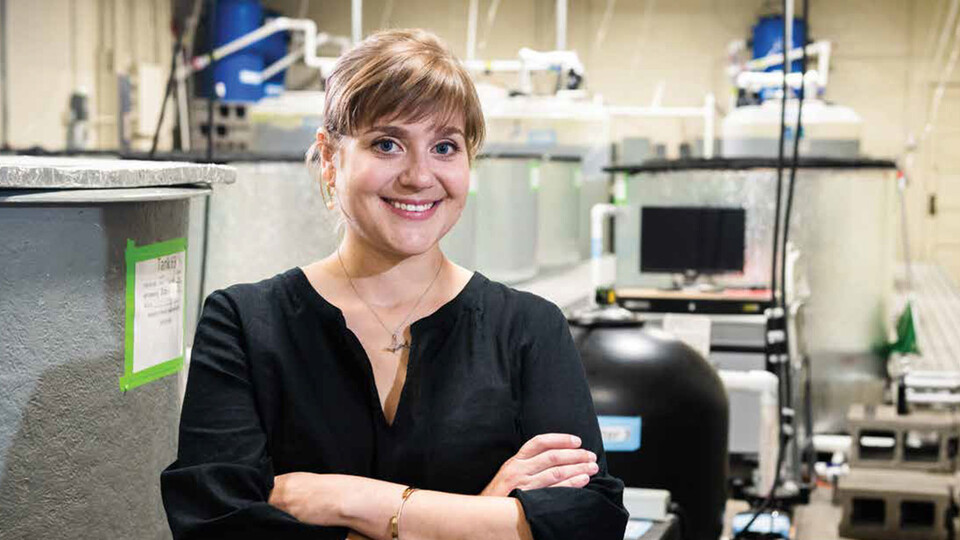

Poletto sees fish ecology as ‘canary in a coal mine’

Who: Jamilynn Poletto, fish physiologist and assistant professor, School of Natural Resources

What: Fish are an indicator species — and may even be a signpost for dangers to human health. Similar to the canaries that were sent down coal mines to detect the threat of dangerous gases that could be hazardous to coal miners, fish can help detect issues in water systems, Poletto said.

She and her research team study how changes in the environment, or stressors, interrupt normal fish behavior. Three main stressors impact fish species in Nebraska: rising temperatures, water level fluctuations and pesticides.

Given the importance of fish to an ecosystem, Poletto also investigates ways to conserve various fish species. Together, this information can reveal how environmental factors alter the health of various fish species, as well as water quality in a given area.

“If fish are sick, it is a really good indication that there is something wrong in that ecosystem. For fish in particular, it is usually associated with water quality. And unfortunately, the water that fish are swimming in is oftentimes the same water that we are drinking,” Poletto said. “So anything that’s going to be potentially detrimental to the health and survival of a fish could be detrimental to us, as well.”

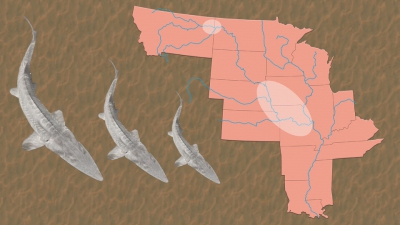

Downstream effects: Sturgeon lifespan, fertility vary strikingly with river conditions

Who: Mark Pegg, professor, School of Natural Resources

What: Pegg’s research found that pallid sturgeon stocked around the lower basin of Nebraska, Iowa and Missouri live an average of 19.8 years — nearly three times shorter than in the upper basin of Montana and North Dakota, where the average was an estimated 56.4 years.

The shorter-lived females in the lower basin also weighed an average of seven times less than those in the upper basin. They also spawned between three and 11 times — well below the range of 13-20 times among females in the upper basin. According to the research team’s estimates, the lower-basin females consequently laid about 10 times fewer eggs over their lifetimes.

“What it really highlights is that we do need to be careful about just willy-nilly stocking or reintroducing fish or birds or mammals into places they may or may not be well-adapted to,” Pegg said.

Scientist establishes concept for soil health management

Who: Bijesh Maharjan, assistant professor of agronomy and horticulture, and soil nutrient and management specialist, Panhandle Research and Extension Center; Saurav Das, postdoctoral research associate; and Bharat Sharma Acharya, Oklahoma Department of Mines

What: Soil health advocates say interest is growing in nurturing the vital natural resource, but there’s no standard way to measure soil health or predict its potential for improvement. Maharjan is proposing a concept — and a name — that could help establish the parameters for measuring baseline soil health and its potential for improvement.

He coined the term Soil Health Gap, the topic of an article that he co-authored and published in the journal Global Ecology and Conservation. The article defines Soil Health Gap as the “difference between soil health in an undisturbed native virgin soil and current soil health in a cropland in a given agroecosystem.”

Maharjan and his co-authors suggest the gap can be determined based on either general or specific soil properties, such as soil carbon levels or aggregates. Scientific advancement in identifying primary soil health indicators and developing soil health index based on these indicators is key to a reliable and quantitative measure of soil health. According to the article, “Information on soil health gap, on a local or broader scale, can help identify areas with the greatest potential to enhance soil health, prioritize efforts, and invest resources effectively.”