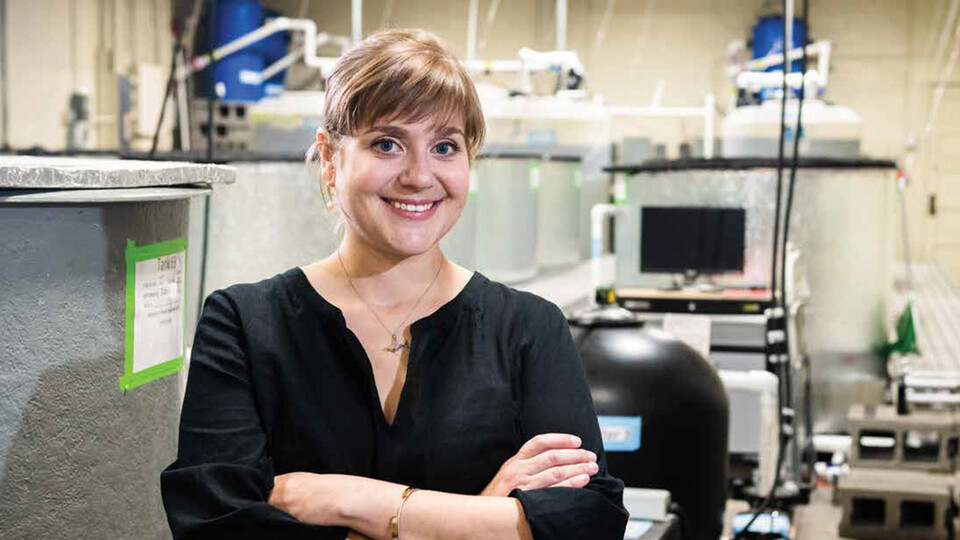

Leanne Gamet, July 7, 2020

Poletto sees fish ecology as ‘canary in a coal mine’

Fish are an indicator species — and may even be a signpost for dangers to human health, says Jamilynn Poletto, a fish physiologist and assistant professor in the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s School of Natural Resources.

Similar to the canaries that were sent down coal mines to detect the threat of dangerous gases that could be hazardous to coal miners, fish can help people detect issues in water systems, Poletto said.

“If fish are sick, it is a really good indication that there is something wrong in that ecosystem. For fish in particular, it is usually associated with water quality. And unfortunately, the water that fish are swimming in is oftentimes the same water that we are drinking,” Poletto said. “So anything that’s going to be potentially detrimental to the health and survival of a fish could be detrimental to us, as well.”

Ecology has become a second language for Poletto. She and her research team specifically study how changes in the environment, or stressors, interrupt normal fish behavior. Given the importance of fish to an ecosystem, Poletto also investigates ways to conserve various fish species. Together, she said this information can help reveal how environmental factors alter the health of various fish species, as well as the quality of water in a given area.

Environmental stressors for fish

Three main stressors impact fish species in Nebraska: rising temperatures, water level fluctuations and pesticides.

Rising temperatures can significantly stress fish because they are ectotherms, or cold-blooded, meaning that their body temperatures reflect the temperature of the water. Rising water temperatures will therefore raise the body temperatures of the fish.

“Every aspect of physiology is dependent on temperature,” Poletto said. “As temperatures begin to increase, everything else begins to increase. For fish, the most notable (change) is metabolic rate.”

When the metabolic rate increases, fish growth also increases. And when fish grow rapidly, their need for food naturally increases — yet a food source is not always available to sustain that growth. Poletto said that researchers often pull fish out of rivers that are overly skinny and ill-looking, which can be an indication that warmer temperatures are increasing metabolic rates. Fish are unable to compensate with enough calories to balance out their high metabolism, and the lack of food causes weight loss and health issues, she said.

Because irrigation is such a key component to Nebraska’s farmland, water level fluctuations are also an issue for fish.

“As we pull water out of the rivers for irrigation and for municipal use, the water levels begin to drop, and fish can actually become stranded,” Poletto said. For example, she said, there are areas of the Platte River that can rapidly go dry. When this happens, fish may not have enough time to move to a new area and often get deserted.

Finally, while pesticides are an important aspect of the farming industry, they may burden fish populations if pesticide levels get too high. Pesticides are maintained at levels that are safe for humans to drink, but fish are much more susceptible to elevated levels. “They start to show abnormalities in behavior, physiology, growth, so we see that first,” Poletto said.

Being aware of specific stressors that are impacting fish in Nebraska habitats is essential, she said, and will be a cornerstone of fish conservation going forward.

Conservation efforts in Nebraska

Many Nebraskans are passionate about being outdoors, with hunting, fishing and watching nature among the advantages of living in the state. According to Poletto, some residents inherently want to be around wildlife populations. This often makes people more receptive to the importance of conservation and environmental restorations.

“I think we need to get the message across that if we don’t continue certain conservation efforts, or if we don’t create new conservation efforts, we are going to lose these endangered fish species populations,” Poletto said.

Moving forward, conservation projects and management will be crucial for species of all ecosystems, but especially for fish species, which represent nearly half of the vertebrate diversity in the world.

“We have this amazing opportunity to study the diversity of fish species,” Poletto said. “For pretty much any physiological property or behavioral property you want to study, there is a fish species that is the shining exemplar of it. Studying fish allows us to continue to look into interesting scientific principles that maybe we can’t study in mammals or in birds.”

A love of wildlife will be a driver for people to keep conservation efforts alive, Poletto said. When people are passionate about something, they typically work hard to keep it — and fish need all the help they can get.

“Endangered fish are not going to heal themselves if we do not help them at this point,” she said. “There are so many human-imposed stressors that we have inflicted upon them. It’s important to keep studying them, because they are interesting and provide information that we didn’t previously know.”

The future of fish conservation

Technological developments in conservation are currently happening at the university. “I think the future of conservation is using technology in really unique and creative ways,” Poletto said. “That is going to come from students who are studying technology and science right now.”

Poletto’s aquaculture laboratory, located behind the Nebraska Tractor Test Laboratory, is making strides toward stronger fish resilience. The lab houses recirculating systems that researchers can use in running tests to learn more about temperature, water quality and oxygen levels in fish.

At the lab, Poletto and her team determine how well and under what conditions fish can swim; the maximum temperatures that fish can withstand; and how well they are able to grow and survive while responding to the aforementioned stressors.

“We rely on the same natural resources that many of the fish and wildlife rely upon,” Poletto said. “If they’re not taken into consideration, we’re not taking our own future into consideration.”