Milk does a body good, as the saying goes, and Nebraska scientists are exploring how to make it even healthier by enhancing its infection-fighting properties.

Jennifer Auchtung

“We know that different parts of a person’s diet can have potential impacts on their microbiome, and this may influence susceptibility to infections with different gastrointestinal pathogens,” said Jennifer Auchtung, one of the main investigators on a new research project led by the Nebraska Center for the Prevention of Obesity-Related Diseases. “One of the questions we asked was whether the molecules that are found in dairy products, especially milk, can change the microbiome and influence this susceptibility to infections.”

Janos Zempleni

Auchtung, assistant professor of food science and technology, is working with lead investigator Janos Zempleni, professor of nutrition and health sciences, on a four-year research project, funded by a $500,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, to study how milk enhances or diminishes pathogenic bacteria.

The new research builds on work Zempleni’s lab has been doing since 2013 to study how nutritional nanoparticles affect the human gut.

“No matter what you do diet-wise, you’re always going to change the gut microbiome,” said Zempleni, NPOD’s director and Willa Cather Professor of molecular nutrition.

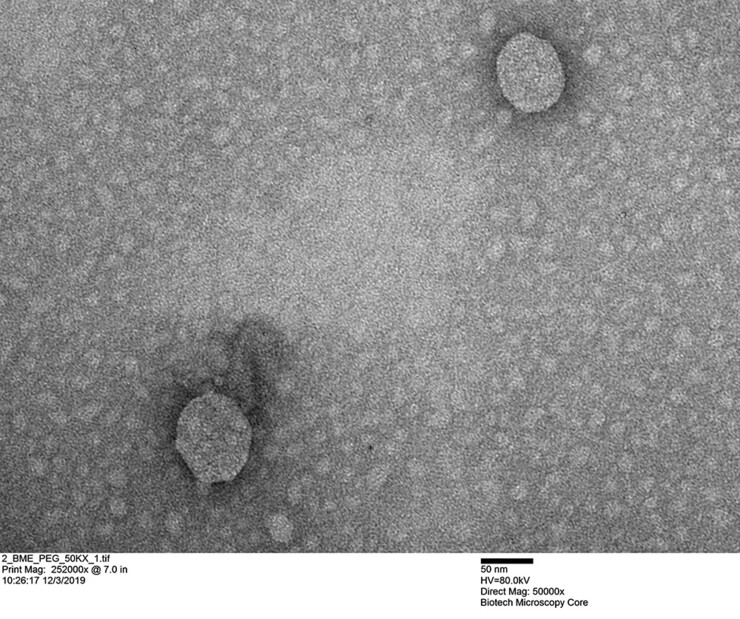

Through natural nanoparticles known as exosomes, milk delivers bioactive compounds to humans. Exosomes facilitate cell-to-cell communication through the transfer of regulatory “cargos” from donor to recipient cells. Some of the exosomes and their RNA cargos from milk are absorbed, but some escape absorption and interact with the gut microbiome, encouraging certain virulent gut bacteria.

Of specific concern in this research are two antibiotic-resistant bacteria that can wreak havoc in the body: Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis (VRE) and Clostridioides difficile, which together cause infections in about 500,000 Americans annually. Over the past 30 years, infection rates of C. difficile and VRE have increased considerably.

VRE can cause severe infections in people who are immunocompromised, such as those who have received organ transplants or are undergoing chemotherapy, Auchtung said. C. difficile is one of the leading causes of hospital-acquired infections and antibiotic-associated diarrhea, which kills up to 15,000 people a year in America.

This project builds on the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s previous research into the gastrointestinal tract, where trillions of microbes — bacteria, viruses, fungi and more — live in what’s collectively known as the gut microbiome. The gut normally acts in concert with the body to regulate organs, develop the immune system, fight disease and metabolize foods. But abnormalities in the gut microbiome are being discovered as factors in many diseases.

At Nebraska and elsewhere, previous research into diet-microbiome interactions has focused largely on the effects of diet on microbial communities without considering genomic changes within these communities. This is the first study to assess the effects of exosomes and their RNA cargos on the selection of trait diversity and mutations that alter the virulence of pathogens such as VRE and C. difficile.

Ultimately, Auchtung said, the research could result in targeted ways to modify diets of people taking antibiotics, perhaps through dietary supplements. Zempleni said the research also could lead to nutritional supplements for infant formulas that improve babies’ health in developing countries.