Tiffany Lee, December 14, 2017 | View original publication

Study shows how brain anticipates social exclusion

Three little-leaguers warm up before the game by tossing a softball around the infield, each player getting an equal share of the triangular routine. After a few minutes, the dynamic shifts.

Second base throws to third, who arcs it back to second, who returns it to third, back to second, back to third. The triangle has become a line. And just like that, first base finds herself vigilantly watching her teammates, each wind-up now loaded with anticipation, then anxiety.

Soon it’s undeniable: The others are excluding her.

New research from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has shown that this awareness of social exclusion can produce spikes in attention-related brain activity before the actual act of rejection occurs. That brain activity suggests the onset of a hyper-vigilant state that can help protect a person’s psyche in the short term but inflict long-term psychological and physiological harm, the researchers said.

The study showed that this attentional spike emerged more strongly in people prone to cognitive reappraisal — the types who tend to ruminate on social interactions, mentally replaying them to either decipher or reinterpret them.

“People are preparing themselves for the worst (in those situations),” said John Kiat, lead author on the project and a doctoral candidate in psychology. “It would be great if the body could tolerate that, but unfortunately, we can’t. We can’t be hyper-alert all the time.

“In that state, the brain becomes tuned to social rejection. If anything in a situation cues social rejection, you’re ready for it; you can respond to it. The problem is that the body can’t run that way for long, and when it does, things start to get off-balance. That’s where you get people having to take anti-anxiety medication or sleeping pills just to down-regulate that sort of response.”

The research team reached its conclusions after analyzing neural responses from 20 college students playing Cyberball, a digital version of catch that pairs a participant with two computer-controlled players. For the first 40 throws, a student nearly always got the ball back within two throws. The experiment then transitioned to an exclusion phase, which ended with each student watching the computer play keep-away for 24 consecutive throws.

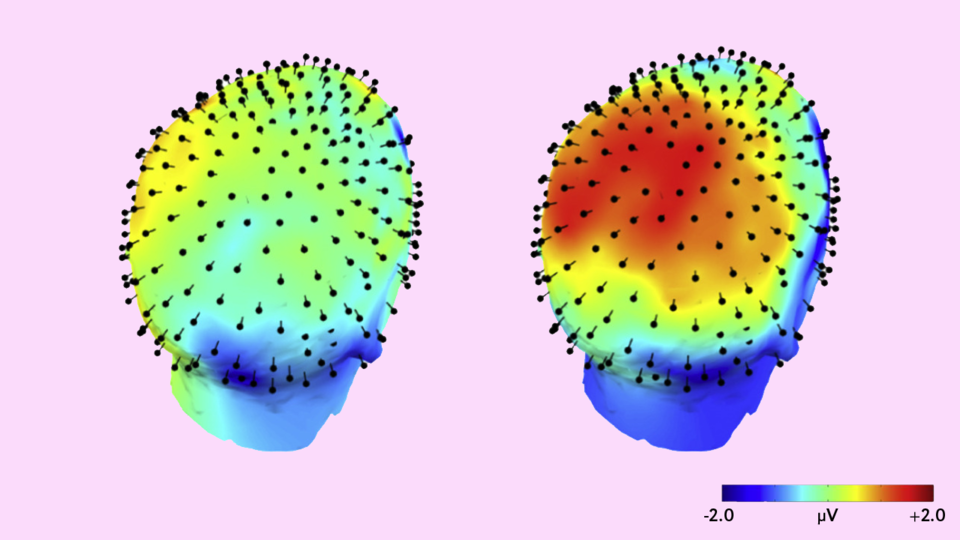

Kiat and his colleagues examined the magnitude of the P3b response – a well-established measure of stimulus-driven attention in the brain – during the inclusion and exclusion stages. The magnitude of P3b increased when a computer-controlled player held the ball in the exclusion vs. inclusion stage, suggesting that students began to anticipate and focus on being left out.

Researchers have already documented the psychological and physiological effects of hyper-vigilance, Kiat said, which range from elevated stress-related hormones in saliva to blood-based biomarkers of cardiovascular disease. But few studies have directly investigated neural links to the anticipation of social exclusion, he said.

“Most research looks at how you respond to rejection,” Kiat said. “But how you respond to rejection is not the same as how you anticipate rejection. Many people, including me, would argue that chronic anticipation of rejection can have much more far-reaching consequences.”

Learning more about the personality traits linked with hyper-vigilance, the types of exclusion that drive it and the specific areas of the brain responsible for it could ultimately help counteract its effects, Kiat said.

“Once you know that attention is really going up, you have a potential intervention target,” he said. “My bias would be (toward) some form of cognitive-behavioral treatment.

“Now that we’ve shown we can identify this, we could also bring people into the lab who have experienced real-world racism or other discrimination and ask, ‘Do those experiences lead to this expression of hyper-vigilance? Can we use these tasks to help assess that and develop a deeper understanding of the impact of social discrimination?’”

Kiat authored the study with Bridget Goosby and Jacob Cheadle, associate professors of sociology. The researchers reported their findings in the International Journal of Psychophysiology.