Scott Schrage, February 28, 2022

Nebraska Sandhills rated as world’s most intact prairie

Study identifies just seven large, intact grassland regions remaining worldwide

“…then you should care about grasslands.”

To speak with the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Dirac Twidwell is to hear the sentiment emerge as a sort of mantra. The reasons preceding the statement, and behind the sentiment, are legion. Protecting signature species from extinction. Maintaining the quality of air and aquifers. Mitigating wildfires and floods. Preserving cultures and livelihoods that echo across generations.

It’s for those reasons that the associate professor of agronomy and horticulture has spent years researching and combating the decline of grasslands, especially the one just a few hundred miles to his northwest: the Nebraska Sandhills. That distance, as relatively short as it is, represents the gulf between what Nebraska is and what it was even a few hundred years ago.

What it was, what the Sandhills remain, is what an ecologist would call a temperate grassland: a mostly treeless, grass- and wildflower-covered region that grounds the surrounding ecology and culture. Or, as Twidwell would describe it, one of the last “true prairies.” Researchers have known for a while that many grasslands, whether temperate or tropical or desert, are shrinking in size or outright disappearing from the planet. But few had tried to quantify the full extent of that disappearance, or the extent to which certain grasslands have resisted it.

“There has not been a complete focus on grassland systems or rangeland systems,” said Rheinhardt Scholtz, a colleague of Twidwell’s and postdoctoral associate of Nebraska. “Grasslands get lumped together in a soup bowl with other vegetation types, and most of the focus goes to the ‘charismatic’ biomes — like tropical rainforests, for instance.

“Grasslands are, in fact, the least protected and most under threat. We reiterate that all the time — but the situation continues to get worse over time.”

Twidwell and Scholtz recently sought not just to clarify the global scope of grassland decline, but to identify the grassland regions that remain whole enough to stand a reasonable chance of being preserved well into the future.

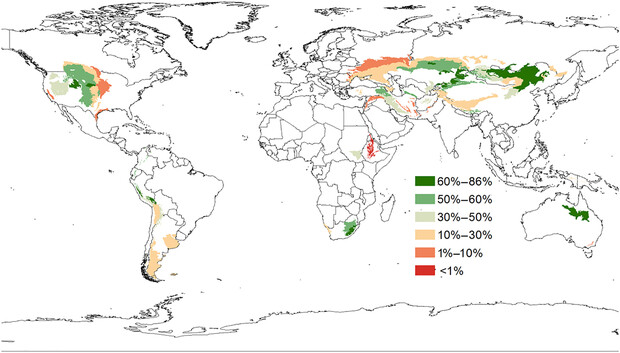

In a new study appearing in the journal Conservation Science and Practice, the researchers found that, of all the temperate grasslands in all the countries in all the world, the Nebraska Sandhills are the most intact. In fact, the duo’s study revealed that the Sandhills are among just seven large-scale grasslands of any type that remain mostly intact. Another resides in the Wyoming Basin, with two others in Asia and one each in Africa, South America and Australia.

But even among that select company, the Sandhills stand apart in two regards. For one, they reside next to the third-most converted grassland region in the world — one that includes central and eastern Nebraska, which has been extensively cultivated for agricultural production over the past 150 years. Despite that, Twidwell said, the Sandhills are also the only major intact grassland currently without a formal conservation strategy.

“I would say that the residents of Nebraska and surrounding states know more about the conservation value and losses in tropical rainforests than in grasslands,” Twidwell said. “But the few relatively intact grassland regions provide the greatest potential for global grassland conservation in this century.

“That most citizens in the Great Plains are unaware of the importance of the last iconic grasslands in their own backyards is a total failure of science literacy in this part of the world.”

The grass menagerie

Appreciating grasslands — giving them the same due that most people reserve for the tropical and deciduous and coniferous forests, for the arid and polar deserts — has never been an issue for Twidwell and Scholtz. The researchers are reservoirs of knowledge that they’re eager to share, especially when it comes to how people, animals and the very planet itself have depended on grasslands, and continue to.

Though not necessarily known for it, grasslands rate as some of the strongest bulwarks against some of the worst consequences of ongoing climate change, Twidwell said. Wildfires, the likes of which have recently engulfed homes in California and Colorado, are less intense and easier for firefighters to manage in intact grasslands than in those becoming dominated by volatile, fire-fueling woodlands. Soils covered with herbaceous plants generally absorb precipitation better than barren ones, lowering the odds of erosion. And roughly 12% of the carbon dioxide that’s captured before it can enter the atmosphere is stashed in those grassland soils, which sequester it away.

“When we’re talking about carbon and climate change, one of the smartest things we can do is keep grasslands green side up,” Twidwell said. “We’ll have greater carbon storage and sequestration by preventing agricultural conversion, especially for the lower-productive grassland regions that are left.”

There’s also the fact that grasslands play host to animal species and migrations found nowhere else on Earth. The eastern edge of the Sandhills serves as the annual pit stop for the aptly named sandhill crane, roughly 500,000 of which arrive between late winter and early spring to rest and refuel en masse before continuing their northerly migration. The Wyoming Basin houses the largest population of pronghorn, which boasts both the greatest speed and longest land migration of any mammal in North America. Another of the world’s seven large, intact grasslands, the Mongolian-Manchurian region of Asia, lays claim to multiple endangered species of eagle, falcon and other raptors.

“Our largest intact grassland regions are strongly tied to some of the most iconic wildlife in the world,” said Twidwell, noting that the population of grassland birds in North America has fallen more than 50% in the past 50 years.

The decline of grasslands is endangering livelihoods and cultural legacies, too. Raising livestock remains the economic and cultural backbone of the Sandhills and other grassland regions whose soils cannot easily sustain agriculture. The nomadic culture that arose around herding sheep and cattle in the Mongolian-Manchurian grasslands, for instance, dates back several thousand years. In South America’s Central Andean wet puna, which sits more than 2 miles above sea level, grazing and agriculture still incorporate certain practices developed by the Incas.

“If we lose grassland biomes, we lose a unique culture,” Twidwell said. “Much of that culture is still tied to Indigenous roots globally. We see that culture erode or even disappear when a grassland gets replaced.”

‘For the first time, there’s evidence for hope’

To better understand the status of landscapes so tied to the past, Twidwell and Scholtz turned to the very pinnacle of modern-day technology: satellites operated by NASA and the European Space Agency. The former provided images of Earth’s surface from 2001 and 2019. The latter offered land-cover imagery only from 2019, but at a higher spatial resolution, with each pixel representing tracts of land just 1/16 of a mile tall and wide. Combined, those resources presented a reasonably detailed then-and-now perspective on how grasslands have changed across the first two decades of the 21st century.

They did so, in part, by allowing the researchers to calculate two metrics that tend to say a lot about the resilience and long-term prospects of a grassland region. One is intactness, which Scholtz explained by pulling up a three-by-three grid of pixels resembling the connected squares of a chessboard. To evaluate intactness, the researchers directed a program to pick a pixel, then analyze it and the eight pixels that bordered it. If any of those pixels were not predominated by grassland, the nine-pixel area was not considered intact.

“Highly intact regions are just more resilient,” Rheinhardt said. “The more intact an ecosystem is, the better it’s able to withstand 21st-century, human-driven pressures.”

By running that analysis on every pixel in a grassland region, the duo was able to calculate the percentage of the given region that remained intact. Of the 70 grassland regions analyzed, 47 are less intact than they were two decades ago.

Scholtz and Twidwell also identified the largest area for which every grass-covered pixel was connected to at least one other such pixel. Dividing that area by the overall size of a grassland then gave the researchers what’s known as the largest-patch index. That index essentially measures how much of a grassland consists of an unbroken core as opposed to isolated patches. By that metric, 95.66% of the Sandhills is connected, with just 4.34% separated from that core.

Most other grassland regions rate much lower on the metric. And much as a chess player’s pieces become vulnerable when surrounded by empty squares or opposition pieces, a fragmented grassland region — one characterized by small islands of prairie — becomes more susceptible to threats on multiple fronts, Twidwell said.

“In Lincoln, the small remaining tracts of tallgrass prairie are surrounded by multiple threats, which means they are high-maintenance. They cost considerably more to manage,” Twidwell said. “In comparison, the Sandhills prairie is more intact, more resilient and has greater potential for large-scale conservation, as long as it remains intact. These types of opportunities are incredibly rare today.

“Knowing the regions that are the most intact, that have unique conservation and cultural value, we ought to be pumping conservation investments into them, because they’re experiencing unprecedented threats. These regions survived the last 100 years of human pressure. Many won’t survive the next 100 years of pressure, we expect, unless we move past our current mindset and stop taking them for granted.”

The gravest immediate threat to that resilience in the Sandhills is the encroachment of woody plants, especially the eastern redcedar tree, which is displacing grasslands grazed by livestock and enjoyed by native wildlife. That encroachment threatens the livelihoods of ranchers and the survival of native species while introducing no real ecological, environmental or economic value of its own. Because more than 90% of the region is privately owned, Twidwell and various partners, including the nonprofit Sandhills Task Force, have appealed to those landowners for help in mitigating the spread of eastern redcedar.

The early returns on those efforts also speak to the importance of the latest analysis, Twidwell said. Many prior studies have presumed that private ownership, especially the presence of domesticated livestock such as cattle or sheep, automatically puts a grassland region at greater risk and lowers its conservation value. The high intactness of Sandhills vegetation, and the extent to which landowners understand that sustainable ranching depends on avoiding the overgrazing of native grasses, challenge that presumption.

“Working lands are critically important to rangeland conservation,” Twidwell said. “There is a long culture of sustainable ranching with domesticated livestock in many regions of the Great Plains and elsewhere in the world.”

Other evidence, though, does underline the magnitude of the challenges facing even the temperate grasslands that seem to be faring the best. As intact as they are, the Nebraska Sandhills have still given ground in the past 20 years. So, too, have the two other temperate grassland regions that rank as North America’s most intact: the Flint Hills of Kansas and a short-grass prairie spanning parts of Montana, Wyoming and the Dakotas.

“They’re all losing ground to woody plants,” Twidwell said. “We are going to lose those regions if we don’t halt that expansion.

“The evidence shows that we are not doing a good enough job conserving North America’s grasslands. We have to re-evaluate our conservation mindset if we are actually going to prove that we can conserve this biome within a private-lands ideology.”

A couple of years ago, Twidwell was invited to serve as a science adviser for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, which tasked him with developing new science-based solutions to managing grassland threats. In that role, he’s been heartened to witness landowners, community leaders and policymakers taking the issue more seriously, and considering more conservation-based initiatives, than he’s ever seen in the Cornhusker State.

That collaboration has yielded a national framework for conserving the grassland biome — the first of its kind in the United States — and a Great Plains Grassland Initiative in Nebraska and surrounding states. Conservation-minded communities across Indigenous lands, Canada, the United States and Mexico, meanwhile, have drawn up a Central Grasslands Roadmap for North America.

But Twidwell is far from content and nowhere near complacent. To slow up now, he said, would be to cede further ground at a time when every acre lost may be lost for good.

“The pace of collapse is far outpacing our strategy, our management,” he said. “Nobody has successfully proposed a plan to halt the collapse of this biome — which means that, at best, we will have some large, intact regions left, but at worst, we may have only some islands remaining, just a semblance of the Sandhills and other grassland regions. And that’s the story of grasslands throughout the world.

“The question becomes: Do we recognize why big, intact grasslands are valuable, what they provide, the culture that thrives with it? And are we going to finally start doing something to conserve their legacy? The Nebraska Sandhills represent one of the best chances in the world to do that.”

Agronomy and Horticulture Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources