Center for Digital Research in the Humanities

Dan Moser, February 1, 2021

Researchers exploring Whitman’s journalism for clues to his poetic vision

People remember Walt Whitman primarily as America’s national poet, but he was a journalist, too, and much of that work was published anonymously. University of Nebraska–Lincoln researchers are working to lift that anonymity to provide a more complete picture of a man who wrote about issues that still resonate today.

Funded by a three-year, nearly $250,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the research team’s “Walt Whitman’s Journalism: Finding the Poet in the Brooklyn Daily Times” will focus on Whitman’s output as an editorial writer for the Daily Times from 1856-1859, a period of wrenching national division that was about to result in the Civil War. The first two editions of his landmark “Leaves of Grass” had just been published, and he was on the cusp of a huge expansion of his poetic vision.

Whitman had worked in various roles and for various newspapers in the New York City area since the 1840s, said Kenneth Price, co-director of the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities and a longtime Whitman scholar who is the grant’s principal investigator. In fact, he worked as a journalist for much of his life. It’s believed he may have written as many as 1,200 editorials, most of them unsigned, for the Daily Times in the years before the war.

“He was at his most creative and hitting on all cylinders, doing some of his most radical work as a poet,” Price said, “so if we can identify the unsigned editorials … we’ll have a huge trove of material to better understand Whitman as a creative force.”

Kevin McMullen

“We know Walt Whitman the poet,” said Kevin McMullen, research assistant professor of English and one of the lead editors for the grant. “But in the 1850s, most people would have known Walt Whitman the journalist.”

“Whitman is a ‘cosmos,’ thinking grand thoughts” that he’s expressing in his poetry, McMullen said. “But he’s also interested in the most mundane mixture of life. That mixture is part of the mystery of ‘Leaves of Grass’… He had learned to be an observer (by) being a journalist.”

Much of Whitman’s Daily Times output likely focuses on the same grist a newspaper editorialist focuses on today — local politics, infrastructure worries such as bad streets or sanitation, and so on. But Price and McMullen said they expect to see some of his newspaper work addressing the national issues of the day, too, especially since the 1860 edition of “Leaves of Grass” is notable for greatly expanding his vision.

“Somewhere within the thousands of editorials printed by the Times between 1856 and 1859 — editorials that, day by day, tracked an unfolding national crisis — lie Whitman’s own musings on the nation’s unraveling. In his notebooks, the poet revised his poetry; in the Times, we believe he etched ideas for the nation’s salvation,” the researchers wrote in their grant proposal.

Plumbing this phase of Whitman’s life — one of the least understood periods of his work — won’t necessarily burnish his legacy. Researchers already have identified earlier Whitman newspaper editorials, including a series that opposed public funding for Catholic schools that employed nativist, anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic language.

“People thought, ‘Surely that’s not the Whitman of “Leaves of Grass,”’” McMullen said. “We tested those with tools we’re using, and in fact it was Whitman.”

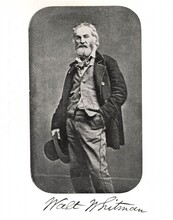

Walt Whitman

Whitman notably became more conservative, even reactionary, on issues of race later in his life, said Price, Hillegass University Professor of American Literature.

“It’s very tricky to get it right with Whitman, trying to be both sufficiently sympathetic and understanding that he’s a 19th-century figure where different norms are in the air, and at the same time recognizing that if we don’t call out shortcomings, then maybe we’re complicit in an ongoing, unresolved racism that has been in the bones of America since the beginning,” Price said.

“He’s the national poet both because of his achievements and because he reflects our cultural shortcomings and ills … majestic in its aspirations and hugely frustrating in its shortcomings.”

For decades, the attribution of anonymous pieces to Whitman rested on relatively subjective methods that mainly involved the detection of some sort of “Whitmanian” voice or tone in a given piece.

This project will use a much more sophisticated system, applied by an analyst at partner institution Marshall University, that compares bodies of texts from unknown authors to bodies of texts by known authors, looking for patterns and similar phraseology, McMullen said.

Rather than comparing frequently used words, the software compares most frequent three-character strings of copy.

“Comparing at that level is more helpful in identifying the author when working with small chunks of texts,” McMullen said. “Some of these editorials are just a few paragraphs.”

The researchers believe this method will be a new tool for studying authorship attribution and serve as a model for other scholars or projects confronted with similar cases of uncertain authorship, even when only a relatively small sample of text is available. One example: Abraham Lincoln scholars hope to identify pieces they believe he wrote during his legal career in newspapers in Springfield, Illinois.

Ultimately, the editorials identified as Whitman’s will be transcribed, encoded, annotated and made available on the Walt Whitman Archive website.

In addition to Nebraska and Marshall, participating institutions are Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, the University of Iowa, New York University, the University of Idaho and the Pedagogical University of Kraków, Poland.

Center for Digital Research in the Humanities Digital Humanities English History Journalism