Cory Matteson, March 17, 2020

Husker who coined ‘flash drought’ helps define emerging phenomenon

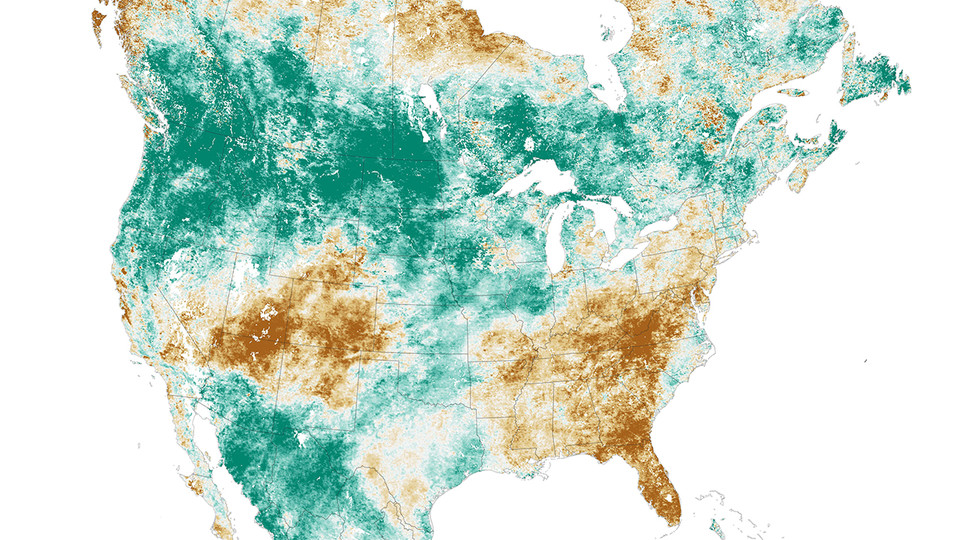

From late August through early October of last year, drought engulfed much of the Southeast United States in a way that many don’t expect drought to behave — suddenly.

Drought throughout the Southeast spiked from covering about 6% of the region to 44% in less than a month. While many droughts embody the common description of the natural disaster as a creeping phenomenon, taking months or years to develop, the Southeast drought grew widespread and severe in a matter of weeks.

It was a classic flash drought, as defined in a new research paper that seeks to clarify what flash drought is and how to better predict it.

Mark Svoboda, director of the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, is credited with coining the term in the early 2000s. Svoboda said he initially used the phrase to help explain to a USA Today reporter that an early-2000s drought in the southern Plains was developing with unusually rapid intensity.

“I wanted to find a term that would resonate for this quicker-developing drought, and ‘flash drought’ just popped in my head, as I thought people could relate it to their knowledge of flash floods,” Svoboda said. “And that took off like wildfire.”

Svoboda is among the 22 authors of a wide-ranging study on flash droughts that was published March 2 in Nature Climate Change. The paper is the end product of a September 2018 workshop where drought experts from around the world gathered at the Aspen Global Change Institute to address sub-seasonal-to-seasonal prediction and flash drought.

A flash drought, as defined by the American Meteorological Society, is “an unusually rapid onset drought event characterized by a multi-week period of accelerated intensification that culminates in impacts to one or more sectors,” such as agricultural or hydrological impacts.

As part of the team that wrote the definition, Svoboda said the Nature paper helps to clarify what a flash drought is (and isn’t), sets guidelines on detecting that one has occurred, and explores ways to improve monitoring and predictions.

“The growing awareness that flash droughts involve particular processes and severe impacts, and likely a climate change dimension, make them a compelling frontier for research, monitoring, and prediction,” the authors wrote.

“It’s a complex problem and we want to treat it in a complex way,” Roger Pulwarty, senior scientist in the NOAA Physical Sciences Division, said during the 2018 workshop. “It’s not easy to characterize a flash drought, and they’re not the same as saying, ‘We have a hurricane of intensity X or Y.’”

In the paper, the authors establish three principles that apply to flash drought: that it involves a rapid onset, that its intensification rate is high, and that the event reaches enough severity to qualify as a drought. Then they proposed two definitions of flash drought — one that applies internationally, as well as for prediction and research purposes, and another that applies to U.S. monitoring.

The international-prediction definition is based on an experimental drought monitoring and early warning guidance tool called the Evaporative Demand Drought Index. The tool examines differences in atmospheric evaporative demand — essentially the drying of the atmosphere — over a given time period. If there is a 50% or greater increase in drying over a two-week period that is sustained for at least two more weeks, according to the paper, a flash drought can be declared.

The U.S. definition is based on the U.S. Drought Monitor, a weekly drought map jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. When the U.S. Drought Monitor reports a two-category change of drought over a two-week period, and that change is sustained for another two weeks, a flash drought can be declared.

The authors wrote that the next steps will be to apply these definitions retrospectively to verify their accuracy in describing unusual, significant drought events that occurred well before the flash drought term was coined and interest in studying it spiked. The definitions could be further refined to reflect impacts that occur in specific regions, the authors wrote.

The paper also examines specific challenges of predicting flash droughts and providing early warning of their arrival, such as forecasting precipitation deficits over sub-seasonal time periods. Svoboda said that developments in satellite technology are helping experts more quickly assess conditions like the ones that led to the 2019 flash drought in the Southeast.

“We have to trust this new breed of indicators that are looking at stress or demand that we can’t even see with the human eye,” Svoboda said. “These tools are looking at indicators of plants that are seen by a sensor that the human eye doesn’t denote until it’s yellow and wilting. The satellite can see that stress in the plant before it shows visible signs to the human eye.

“It takes a change in mindset to evaluate, trust and integrate these new tools into the Drought Monitor process in order to be using the state of the science and being more responsive to these rapid-onset flash droughts.”