Special Education and Communication Disorders

Scott Schrage, October 7, 2020

Rodgers turns gaze on overlooked phase of stuttering: adolescence

As someone who has stuttered for as long as she can recall, Naomi Rodgers knows well the vicious cycle it can trigger.

The words flow fine for a while, to the point that a listener might have no reason to expect otherwise. Eventually, though, a syllable catches in the throat, repeating, refusing to leave. Even subconsciously, the expression of the unprepared listener can shift out of neutral and into confusion, or surprise, or pity, or impatience.

“As you can imagine, this has a huge effect on the speaker who stutters,” said Rodgers, assistant professor of special education and communication disorders at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. “They’re struggling; they know that their listener is noticing that something is going wrong in the interaction, and that places more stress on the speaker to stop stuttering or to make it through really quickly, just to end the awkwardness.”

Rodgers

Stuttering is an inherently social phenomenon. Rodgers stutters only when speaking in the presence of other people, as do most who stutter. The force of those social dynamics — as contributor to and consequence of stuttering — can multiply in adolescence, when status takes on outsized importance and any interaction can become an exercise in self-consciousness.

“I think it’s unfair to assume that adolescents are just older children or younger adults,” Rodgers said. “It really is this period of development that is hallmarked by huge amounts of neuro-biological changes. A lot of those changes are making teens really sensitive to their social world, so the experiences that adolescents have in those years can have massive effects on how they develop social-emotionally as they move into adulthood.”

Rodgers wanted to know more. But as she searched the research literature, she uncovered just a handful of studies — only one involving teens — that investigated how people who stutter attend to the reactions of those around them. And most of those studies, she found, had methodological issues that limited their relevance and applicability to social situations.

She decided to design one of her own. Rodgers’ experiment would test whether teens who stutter are more prone to vigilance-avoidance behavior: a form of high alert that allows people to quickly detect threatening cues so that they can direct their attention away from those cues and reduce their discomfort.

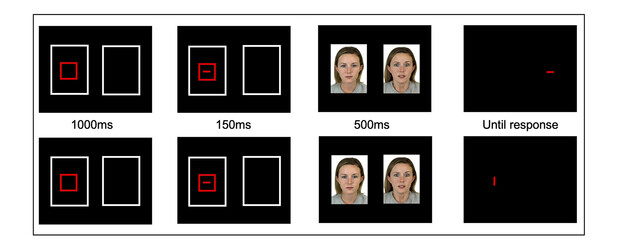

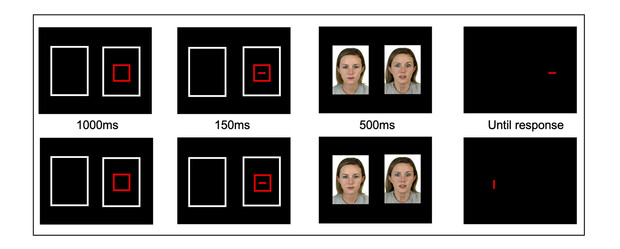

That experiment took the form of a modified dot-probe task. Traditionally, the task involves simultaneously flashing two objects — facial expressions, for instance — on different parts of a screen so that they compete for a person’s attention. When those objects disappear, a so-called probe, usually a dot or other symbol, appears in the place of one object but not the other. Participants are then tasked with identifying some feature of that probe as quickly as possible. Those who are focusing on the object that is replaced by the probe should be able to answer faster than those looking at the other object, the thinking goes, allowing researchers to determine which object most captured their attention.

“But this does nothing to tell us how the participant attended to the negative image,” Rodgers said. “Was their attention quickly captured by it? Did they have a hard time looking away from it?”

In Rodgers’ version, participants aged 13 to 19 began each trial by looking at one side of the screen, where a small line, running either horizontally or vertically, briefly flashed. Another line, running in the same or opposite direction, soon appeared on either the same or opposite side of the screen. Participants were then tasked with identifying, as fast as they could, whether the directions of the two lines matched.

But between the disappearance of the first line and the appearance of the second — a span lasting just half a second — two faces flashed on the screen. One was neutral; the other conveyed a socially threatening expression of either anger or fear.

Though the participants were instructed to focus on and respond to the lines, their response times were a proxy for understanding which face captured their attention. By strategically placing the first and second lines in either the same or opposite locations of the faces, Rodgers and her colleagues could test both sides of the vigilance-avoidance effect — the tendencies to rapidly engage with, and rapidly disengage from, threatening faces.

Rodgers expected to find evidence of both vigilance and avoidance among those who stutter. She did: On average, the 43 stuttering participants answered noticeably faster in the conditions that indicated engagement with and disengagement from the threatening faces. The 43 who did not stutter, by contrast, took roughly the same amount of time under every condition.

But she was in for a couple of surprises, too. Alongside the University of Iowa’s Patricia Zebrowski and Jennifer Lau of King’s College London, Rodgers also had the 86 participants complete the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents. Counter to the team’s expectations, those who stuttered did not report more social anxiety; in fact, both groups approached the clinical threshold for high social anxiety. The similarity suggests that social anxiety was not responsible for the observed differences in vigilance-avoidance behavior, Rodgers said, despite the fact that prior research has linked the two.

“To me, that is fascinating and so confusing, to be honest,” she said with a laugh. “Maybe this vigilance-avoidance, this allocation of attention, gets at a fundamental feature of stuttering. Maybe it has to do with the experience of stuttering above and beyond anything about anxiety.

“I think what’s interesting about this is (that) there are probably unique aspects of stuttering that make these attentional avoidance patterns really salient.”

Rodgers is already pursuing answers to the unexpected questions with support from the American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation and Nebraska’s Mike Dodd, a professor of psychology and expert on eye-tracking technology. Though reaction times alone are informative, eye-tracking can verify exactly where a participant is looking, when, and for how long — details that should reveal more explicit insights into their cognitive processes.

“Eye-tracking is a really logical next step for this,” she said. “I asked around, and people were telling me about Mike: ‘He loves to collaborate with folks. You should reach out to him.’ I’m fresh out of my Ph.D. program — I still have impostor syndrome — so I was like, ‘Gosh, this is really intimidating.’ But he’s been so welcoming and eager to work together.”

‘People who stutter talk beautifully’

Rodgers’ drive to study stuttering developed not just from contending with the ramifications of it, as profound as those were. It stemmed from the frustration she so often felt when working with speech-language pathologists as a child and teen.

“There’s a lot of evidence to show that speech therapists are least confident treating stuttering out of all the populations that they serve,” she said. “And I think it’s because there are just a lot of social-emotional effects of stuttering. It hugely affects your self-esteem, because you know exactly what you want to say, and you feel like you’re having to fight against your body every single time that you want to open your mouth to communicate with somebody. I think it can be intimidating for speech pathologists.”

There’s also the fact that many speech-language pathologists are trained almost exclusively to minimize or eradicate stuttering, even if that outcome can come at the expense of helping those who stutter maintain their sense of identity, Rodgers said.

“You can learn tricks to speak really fluently, but you sound really robotic,” she said as she slackened her speech, drawing out every syllable to demonstrate a common technique. “That doesn’t work for a lot of people, because it just doesn’t feel right. And it doesn’t really get at the meat of the issue, which is learning to speak in a way that still feels like it’s authentic — not feeling like you have to change how you talk just to fit into some societal norm.

“I wanted to do better. I didn’t want other kids who stutter to suffer as much as I did, just meeting up with so many ineffective clinicians.”

It’s partly why Rodgers decided against researching how to modify the speech of those who stutter. But as a self-described “clinician at heart,” she said she does ultimately hope to inform clinical work and improve treatment outcomes.

Helping youth who stutter dwell less on the negative aspects of their social interactions is one avenue she intends to explore moving forward.

“My perspective is: People who stutter talk beautifully, and we can help honor that diversity in their speech. How can we help people develop healthier ways of coping with stuttering and live with stuttering well? That’s my approach.”