Dan Moser, January 27, 2026

Husker researchers make gains on developing synthetic ‘muscle’

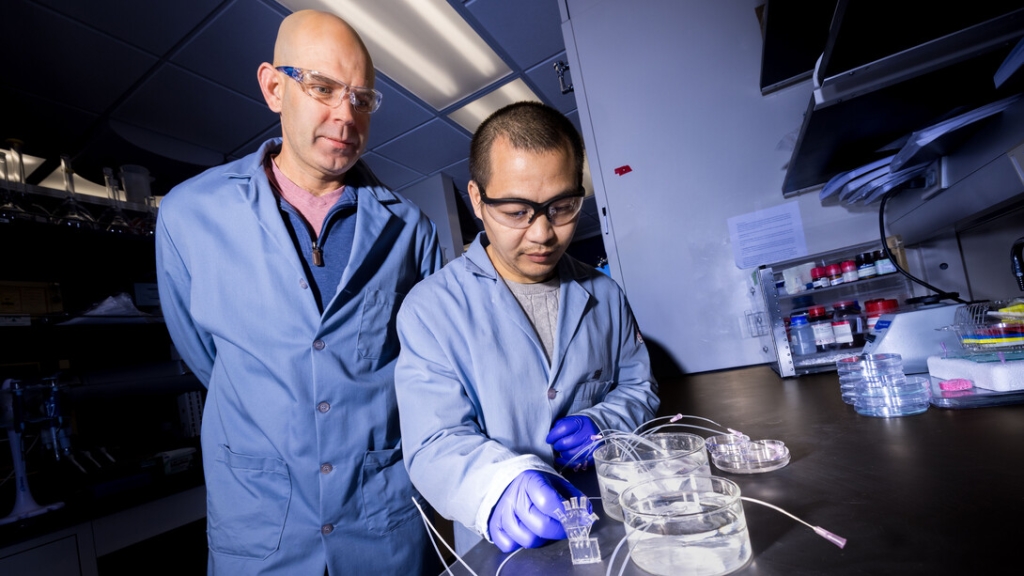

Husker researchers are continuing to make progress on developing a new synthetic material that behaves like biological muscle, an advancement that could provide a path to soft robotics, prosthetic devices and advanced human-machine interfaces.

Their research, recently published in a leading material science journal, demonstrates a hydrogel-based actuator system that combines movement, control and fuel delivery in a single integrated platform.

Biological muscle is one of nature’s marvels, said Stephen Morin, associate professor of chemistry at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. It can generate impressive force, move quickly and adapt to many different tasks. It is also remarkable in its flexibility in terms of energy use and can draw on sugars, fats and other chemical stores, converting them into usable energy exactly when and where they are needed to make muscles move.

A synthetic version of muscle is one of the Holy Grails of material science.

“Artificial muscle has been an elusive target,” Morin said, with much research underway to achieve it, including at Nebraska.

“I’m not going to say that we’ve done that because I don’t think that we have yet, but we’ve demonstrated in this current work two really big principles that work toward the target of some sort of synthetic artificial muscle, and those are microstructure and chemical control,” said Morin, who is also affiliated with the university’s Nebraska Center for Materials and Nanoscience.

Hydrogels — versatile, water-absorbing polymer networks — have shown great potential in soft actuators, but their performance has been limited by their slow response times and the need to operate fully immersed in water.

Morin and his team have been working on a new type of hydrogel-based soft actuator that integrates tiny hydrogel units — known as microgels — with an internal microfluidic “circulatory system” that replicates blood vessels. That approach creates an actuator that can rapidly receive chemical or thermal stimuli while operating in non-aqueous environments.

Ultimately, that could result in a system that responds as quickly and versatilely as biological muscle, enabling fast responses, precise control and practical soft‑robotic functions such as microgripping and multi‑actuator soft robotic “hands” with programmable motions.

Traditional robotic components that rely on rigid motors, wires and batteries still will have a place, but this soft, flexible and water-based synthetic muscle would be better suited to situations where robots interact closely with people or delicate environments, Morin said.

Future versions may adopt fiber-like or tubular shapes more similar to natural muscle fibers, which could help scale up the system for practical use, Morin said.

The team’s work is summarized in Advanced Functional Materials, in an article by Morin and Husker graduate students Nengjian Huang and Brennan P. Watts. The research is funded by the Army Research Office.

Chemistry Materials Science Nebraska Center for Materials and Nanoscience