Tiffany Lee, June 11, 2018 | View original publication

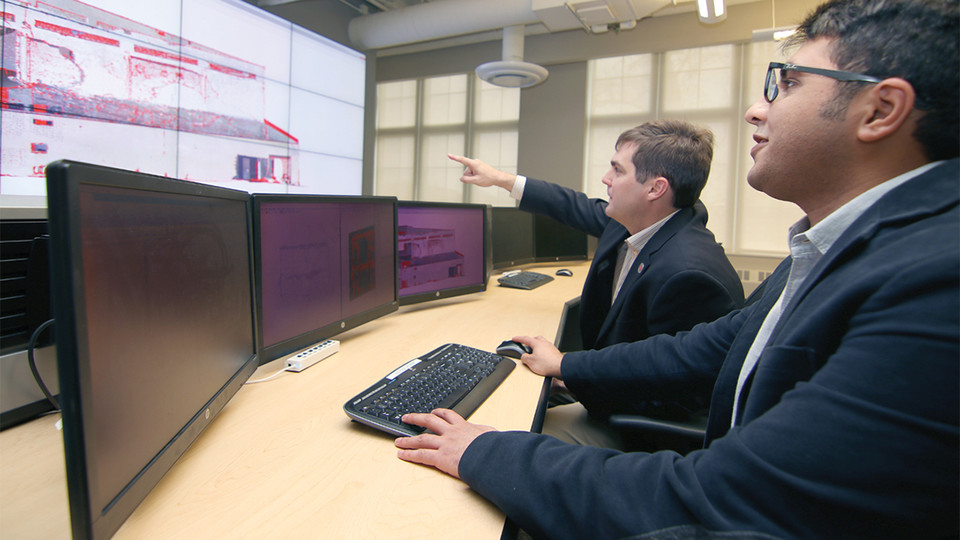

Engineering duo invents software to detect structural damage

University of Nebraska–Lincoln civil engineers have developed 3-D software that can visually identify damage in a range of structures, from bridges in Nebraska to temples in Nepal.

Created by Richard Wood, assistant professor of civil engineering, and Ebrahim Mohammadi, a doctoral student, the software analyzes data collected from remote sensing technology, including unmanned aircraft systems such as drones, and creates 3-D renderings of structures. It uses a blend of statistics and computer science to illustrate areas that are likely damaged.

The software provides an alternative method for conducting visual inspections, which are usually completed up close and in person — a subjective, time-consuming task made potentially hazardous after natural disasters.

“We’re trying to modernize structural assessments,” Wood said. “This technology is unique because it provides a robust, automated way to conduct visual inspections, which remain the most common way to assess structures.”

The software can analyze data gathered under any lighting conditions, including at night — a feature that could enhance accuracy and objectivity, said Wood. By using data collected from drones and lidar, which measures distance using lasers, the software also allows inspectors to assess structural damage while standing safely away.

Wood experienced this safety benefit in Pilger, Nebraska. A tornado hit the town in 2014, killing two people, injuring 20 and destroying buildings. His team visited one year later to assess structural damage using remote sensing technology.

“While our team was collecting data from Pilger Middle School, a section of roof collapsed,” Wood said. “This method allowed us to detect and quantify damage while staying a safe distance away from the building.”

To identify damage across a variety of surface geometries — such as multi-story buildings, bridges and vehicles — the software uses pattern recognition, which categorizes data based on key features.

Refining the software required reams of structural data — about 4,000 gigabytes, Wood said. The team gathered data from Nebraska and in the wake of other natural disasters, traveling to Nepal after the 2015 Gorkha earthquake and visiting Texas shortly after Hurricane Harvey.

While gathering data, the team looked for structures with unique features, including a five-story temple in Nepal, hillsides and potential landslide areas. Each new dataset advanced the software’s capacity to recognize likely damage.

“Our software has improved significantly to reach this point,” Mohammadi said. “As we refine it, we use it for different studies, and it has given us results we can justify.”

Wood and Mohammadi are now working with NUtech Ventures, the commercialization affiliate of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, to identify companies interested in further developing it for commercial use.

“We are very interested in continuing this research,” Wood said. “Working with NUtech has helped us understand what industry is looking for and has helped us refine our scope. It has also changed how we present our work — the language we use and how to best present it for specific audiences, presentations and even funding proposals.”

The team’s research is funded by a Layman Award from the Office of Research and Economic Development. Learn more about this technology.