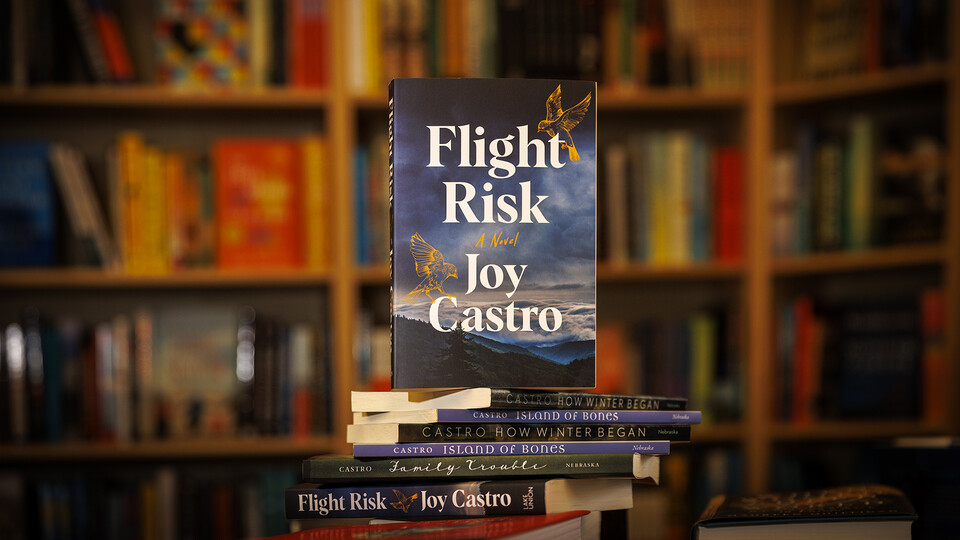

Joy Castro’s new novel, “Flight Risk,” is a thriller that incorporates some of the mystery genre’s classic elements: cryptic phone calls, slashed tires and a handsome man with dangerous vibes.

But beyond its sheer entertainment value, the book, which is Castro’s sixth, carries its intellectual weight: Woven throughout the story are observations on race, socioeconomic divides, rural and urban clashes, and climate and environmental issues, which are some of Castro’s literary trademarks.

Castro, who is Nebraska’s Willa Cather Professor of English and ethnic studies, is becoming a master of merging the fun with the serious. She began her foray into mystery fiction in 2012 with “Hell or High Water,” a Nebraska Book Award winner that follows journalist Nola Céspedes through post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans as she reports on the hundreds of sex offenders who went off the grid in the storm’s aftermath. Castro followed that up in 2013 with a partner novel, “Nearer Home,” which tracks Nola as she investigates a murder.

Reviewers and readers praised both books for their edge-of-your-seat thrill – but also for their commentary on hard-hitting topics like sexual violence, class mobility and cultural identity.

“Flight Risk” extends this trajectory, with a suspenseful plot that unfolds against a backdrop that highlights many of our society’s biggest social, political and environmental issues. Castro said she never wants her novels to be didactic – but she doesn’t want to entirely shed her “professor” hat, either.

“My books have been described as ‘beach reads for smart people,’ and I really like that, because I try to create page-turners that are still intellectually rich and provocative,” said Castro, who directs the university’s Institute for Ethnic Studies.

“Flight Risk,” which Castro has been developing since 2013, tells the story of Isabel Morales, a Latinx artist living in Chicago who is married to a pediatric radiologist. The couple lives a life of luxury marked by dinner parties, charity galas and an expensive condo overlooking Lake Michigan. But readers learn that Isabel’s life is a carefully maintained veneer: Unbeknownst to her husband or her Chicago social circle, her childhood and early adulthood were marred by poverty, instability and intrafamily violence that altered her life trajectory. The novel follows Isabel as her past and present converge, precipitated by her mother’s death in an Appalachian prison.

Castro sat down with Nebraska U’s Tiffany Lee to discuss some of the book’s deeper themes, her tips for aspiring writers and her thoughts on the key role that the arts and humanities plays in advancing research. Portions of her responses (below) were condensed for length and clarity.

Many of the book’s themes have been at the forefront of our country’s political and social life for a long time, particularly in recent years. How did contemporary events shape your thinking as you worked on the book and developed Isabel’s story?

I’ve actually been thinking about most of these things for decades. I was aware of climate change in the ‘80s, when people were first talking about it and scientists were first saying it’s a real thing caused by humans. I’ve always loved nature, so I’ve long been interested in environmental preservation and conservation.

Race and social justice are things I’ve been working on for my whole career, and that I was sensitive to because of my own family background, which is complicated in that regard.

I didn’t have language for it, or a critical apparatus for thinking about it, until quite late in graduate school. People were not talking about race at the universities I attended when I was there: Trinity University in San Antonio and Texas A&M. But those issues mattered to me, so I did readings on the side – reading the work of Latina authors, for example. And thank goodness I did.

I grew up in poverty, so class issues have always been visible to me because I saw what a struggle that was. I wasn’t always in poverty as a child, but during the years that we were, it was very difficult – food stamps, insecurity and some really brutal situations. It affects everything in your life: What you have access to, your education, your socio-cultural capital. I couldn’t have articulated that at the time, but it’s something I always noticed. As I grew and went through my university education, I kept watching for things that would help me think about those differences in a society that always claimed it was a level playing field for us all.

Another theme throughout the novel is just how wrong we can be when we make assumptions about other people. Throughout the book, Isabel makes assumptions about her husband, her family members, her high school acquaintances and even a group of strangers she sees in a restaurant. Most of these judgments turn out to be wrong. What inspired you to wrestle with the hazards of quick assumptions in this book?

The book is definitely about really seeing, really reading people. It’s about re-vision – really seeing again. There is a part in the book where Isabel is thinking that maybe reading people is not even the way to go about interacting: to instead see, and let yourself be seen, so there is a move away from judgment and the quick stereotyping that seems so easy. We’re so often wrong. You see one facet of a person, and you build a whole character sketch. Most of us are far more complicated. I’m pretty fascinated by how layered and ever-changing we all are.

November was National Novel Writing Month. To the aspiring writers on campus, what advice would you provide about how to find time to write and keep creativity flowing, even when day-to-day life is busy?

I’d say that you don’t find time to write; you make time to write. You have to prioritize writing, and you have to carve out space for it in your life. There are other things you let go of so you can write instead, so you just have to figure out what you’re willing to sacrifice and strike that bargain with yourself.

I like writing when I first wake up in the morning, before I check email or social media or listen to any news. I write with my dream-brain still switched on, my unpolluted brain. My own words far flow more easily when I haven’t yet been distracted by all the words and views of the world.

“Flight Risk” addresses at least four of the thematic areas the university is addressing through its Grand Challenges initiative: anti-racism and racial equity, climate resilience, early childhood education and development, and health equity. How would you characterize the role of creative work, and other scholarship in the arts and humanities, in contributing to the university’s efforts to pursue solutions to the Grand Challenges?

Yes! I’m so excited about this new venture – and in fact, I’ve been publishing books about these four themes – along with class injustice and sexual violence – since 2005. I’m very glad that the university is now prioritizing the funding of work that might contribute to solutions for these problems, which are absolutely crucial for life on Earth and the potential for lasting peace.

I won’t personally benefit from any of the new Grand Challenges grants, which require professors to work collaboratively in teams, because, as a writer, I prefer working solo, and the Grand Challenges initiative is not funding solo work. Yet it’s excellent that the university is now funding work that needs to be done collaboratively on these fundamental problems, and I’d characterize the role of the arts and humanities in solving them as essential, because artists and humanities scholars tell the stories that make large-scale problems comprehensible and emotionally accessible to non-experts. We can put a human face on massive problems, like climate catastrophe and poverty, and this can galvanize people into action. Artists imagine different ways of living and make those realistic on the page or stage or screen, so people can more easily envision various alternatives to the status quo. I think it was the poet Ezra Pound who called artists “the antennae” of the human race – the sensitive, dreamy ones with all our nerves perpetually a-quiver: the advance guard, the human seismographs who feel things first and make them readily legible to others.