Tiffany Lee, November 4, 2025

New facility, NSF grant advance smart building technology

On the west lawn of the Peter Kiewit Institute in Omaha stands a 1,000-square-foot building that, with its gray siding and simple rectangular shape, appears nondescript at first glance.

But in reality, it is a state-of-the-art laboratory, designed to simulate the construction of modern commercial buildings and equipped to allow researchers to manipulate various parameters — like lighting, acoustics and temperature — and assess occupants’ response, including physiological parameters like heart rate and skin temperature. The facility, called the Human-centered Integrated Building Operations, or HIBO, Laboratory, is home to University of Nebraska–Lincoln researchers who are working to shape the next generation of smarter, more sustainable and more comfortable buildings.

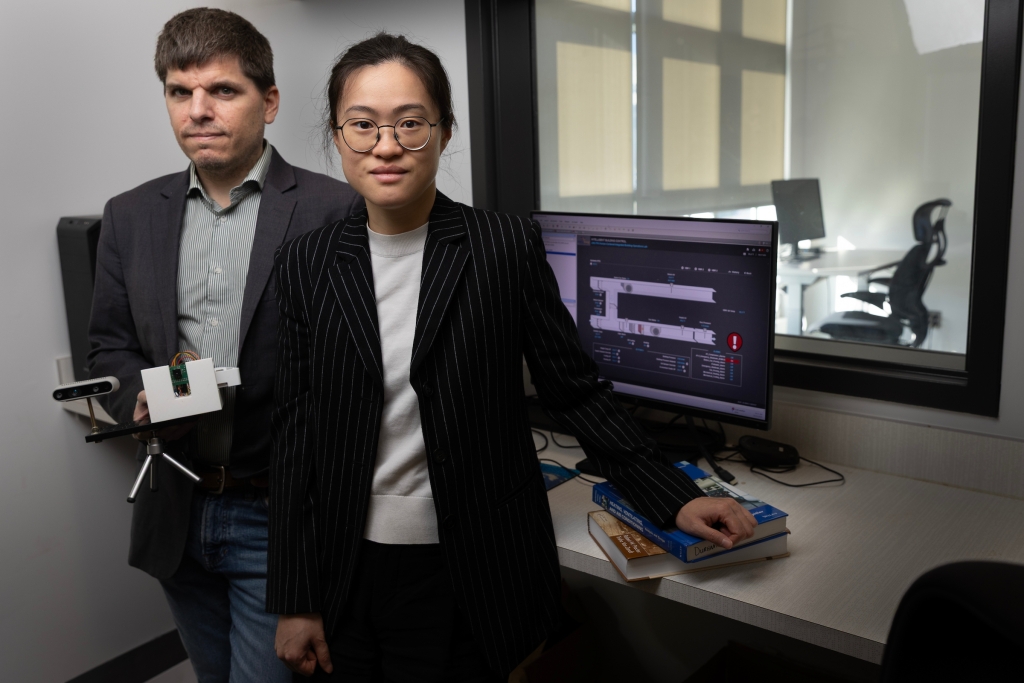

“This building is among only a few in the United States that allow us to study human-building interaction, smart building technologies and human perception of indoor environments,” said Iason Konstantzos, founder and director of the HIBO Lab and assistant professor in the Durham School of Architectural Engineering and Construction. Xiaoqi (Clare) Liu, also an assistant professor in the Durham School, co-directs the lab.

Now, the researchers have an opportunity to use the laboratory, constructed in 2023, for a new project. The team recently received a three-year, $1.2 million grant from the National Science Foundation to develop an artificial intelligence algorithm that dynamically and autonomously operates building systems in a way that strikes a balance between energy efficiency and occupant comfort. The algorithm will merge three types of information: data from building sensors; knowledge about building systems, engineering and physics; and human feedback from building occupants.

Integrating these different elements into a single algorithm distinguishes the approach from other AI-based smart building strategies and paves the way for a tool flexible enough to work in a wide range of buildings, which as a sector are responsible for over 35% of the nation’s carbon emissions.

“Usually, these AI algorithms are more data driven, exploring the trends between different types of data in the building,” said Liu, the project’s principal investigator. “But in real-world settings, high-quality data can be difficult to collect. For our approach, we’re infusing our fundamental knowledge of engineering into the AI to optimize the operation of the building’s equipment, save energy and provide comfort requiring the minimum amount of data possible.”

Exclusively data-driven control is a challenge because even in a modern commercial building, there are not enough sensors to paint a complete picture of the building’s operation and to account for external factors like the weather or shade from neighboring structures, for example. And there is no easy way to continuously collect occupants’ opinions: Is the building too hot or cold? Too bright or dim?

That’s why the team is not only embedding engineering knowledge into the AI tool; they’re also accounting for people’s preferences. Integrating human perspectives into the tool is key because energy efficiency means little without occupant comfort. The researchers will collect input through surveys and observation of how occupants adjust their environment under various conditions.

“In any automated control system in the real world, people have the option to override the settings if they don’t like them,” Konstantzos said. “If people continuously override the settings, you then have a very expensive, big commercial building that is running without consideration of energy objectives at all — and then we are back 50 years in terms of our energy footprint.”

The tool will also provide occupants real-time updates about the building’s energy performance and inform them about how they can boost energy efficiency. The team envisions deploying these alerts through computer notifications initially, then later via phone and watch messages.

If successful, the algorithm would overcome one of the most persistent hurdles to developing smart building technology: scalability. Because buildings are vastly different in terms of design, location, occupancy and more, researchers have struggled to generate a broadly functional AI tool. But Liu and Konstantzos’ “smarter” algorithm may be a step toward a solution.

“We’re figuring out what needs to happen in order to transfer this new knowledge to the real world, to places with completely different climates, building geometries, construction and people,” Konstantzos said. “I see that as a challenge, and if we are able to make a step forward in that direction, I think that would be the coolest part of this project.”

The grant will also support Konstantzos in developing a more efficient system for commissioning buildings, which is a calibration and quality assurance process ensuring that a new structure operates as intended. His approach uses a low-cost network of sensors that play dual roles. Not only do they allow engineers to test a new building’s performance prior to opening; they also collect a robust data set that will catalyze performance of the team’s AI tool.

The researchers will test the commissioning scheme and the algorithm in the HIBO Lab. Eventually, they hope to leverage the Durham School’s network of industry partners to test drive the systems in real-world commercial buildings.

The team also includes former Husker researcher Dung Tran, now at the University of Florida.

Architecture Durham School of Architectural Engineering and Construction