Troy Fedderson, November 5, 2025

Batelaan’s quantum curiosity draws national recognition to Nebraska

Nebraska’s Herman Batelaan has been awarded the 2026 Davisson-Germer Prize for cutting-edge work revealing how electrons behave in the world of quantum physics.

The prize, presented since 1969 by the American Physical Society, recognizes outstanding work in the fields of atomic physics and surface science. It is named for Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer, whose pioneering electron diffraction experiments confirmed the wave nature of matter.

“The Davisson-Germer Prize is one of the highest honors in atomic physics, and Dr. Batelaan’s selection speaks volumes about the depth and originality of his research,” said Pat Dussault, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. “His discoveries, which enhance understanding of the fundamental interactions between light, electrons and atoms, exemplify the kind of bold, curiosity-driven research that elevates our university.”

Batelaan, the Burton Evans Moore Professor of Physics at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, is being recognized for his role in developing the field of free-electron quantum optics. The award cites his work in three fundamental areas — the Stern-Gerlach effect for electron beams, the first demonstration of the Kapitza-Dirac effect and expanded understanding of the quantum physics of the Aharonov-Bohm effect.

The honor will be presented at the APS March Meeting in Denver.

Batelaan, who joined the Nebraska faculty in 1999, said he was “stunned” to learn he had been chosen for the prize, which is among the most prestigious honors in atomic physics. He is the first Husker to receive the award.

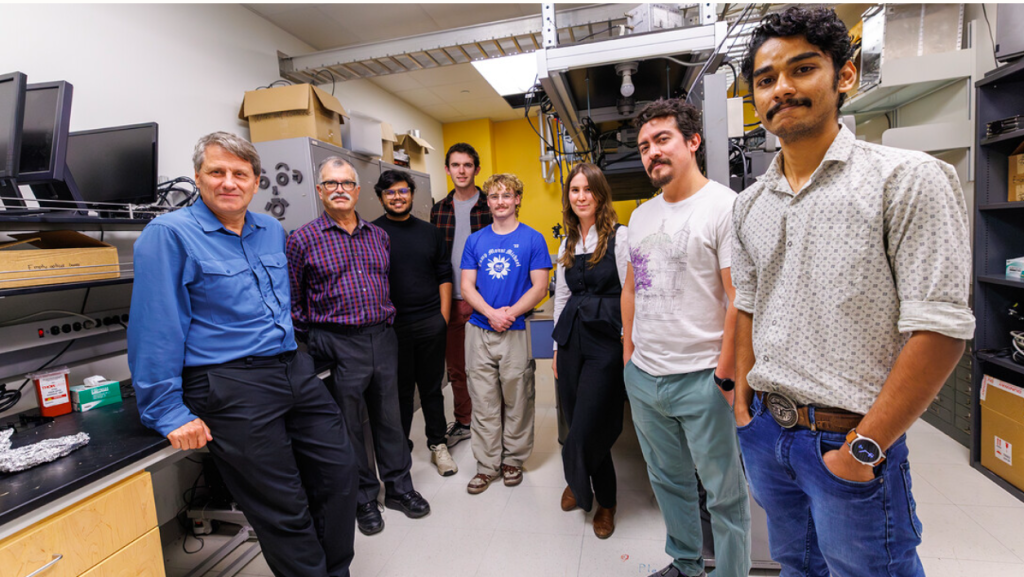

“There are so many amazing scientists out there doing wonderful work — I never expected this,” Batelaan said. “It’s a tremendous honor, but I really see it as recognition of the incredible graduate students and colleagues who made these discoveries possible.”

Much of the research cited by the APS took shape in Batelaan’s lab at the university. His group has explored fundamental questions in quantum mechanics, including how electrons behave in experiments once thought impossible. The team’s work has combined theory and experiment — from uncovering a decades-old error in the conventional understanding of the Stern-Gerlach effect for electrons to conducting the first direct demonstration of the Kapitza-Dirac effect, in which light acts as a diffraction grating for electrons.

Batelaan’s research on the Kapitza-Dirac effect reversed the concept demonstrated in the famous 1927 Davisson-Germer experiment — the namesake of the APS prize. That experiment, which helped earn Davisson a share of the 1937 Nobel Prize in physics, showed that electrons can diffract as waves when they encounter matter. Batelaan’s team demonstrated the opposite — that electrons can diffract from light, which acts as a kind of optical grating.

“None of this happens in isolation,” Batelaan said. “These experiments rely on talented students, engineers, computer specialists and supportive colleagues. It’s very much a team effort.”

Born and educated in the Netherlands, Batelaan earned his undergraduate and doctoral degrees from Leiden and Utrecht universities before continuing research appointments in New York (working with Harold Metcalf, a pioneer of laser cooling), Austria (with Nobel laureate Anton Zeilinger) and Eindhoven. He came to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln to work on polarized electron studies with physicist Tim Gay, Willa Cather Professor of Physics and Astronomy. He later established his own lab focused on quantum optics and foundational physics.

For Batelaan, curiosity has been the driving force of his nearly four-decade career.

“I’ve always been drawn to questions that seem simple but aren’t fully answered,” he said. “When you dig deeply enough, even the things that appear settled in textbooks still hold mysteries. That’s where discovery lives.”

In addition to his research, Batelaan said he takes pride in mentoring the next generation of scientists — many of whom have gone on to careers in academia, industry and beyond.

“My job is a privilege,” he said. “I get to explore new ideas and teach bright students who are eager to learn. Watching them succeed — that’s as rewarding as any award.”

Batelaan continues to push the boundaries of quantum theory and experiment. He is co-authoring a book on the electron double-slit experiment and collaborating internationally on projects that test the limits of foundational quantum principles.

He currently leads two experiments funded through a single National Science Foundation grant. One explores the quantum measurement problem, where particles can exist in multiple states but “choose” a single outcome when measured. The other tests whether the Pauli exclusion principle still holds when a quantum wave is disturbed faster than light can travel across it.

Learn more about Batelaan’s research.