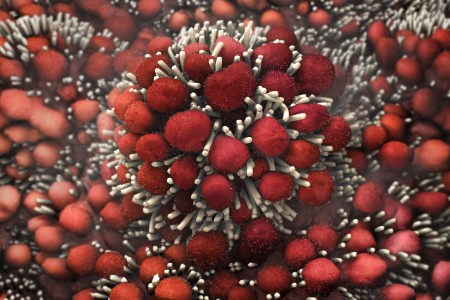

As bacterial villains go, E. coli O157:H7 is among the best known. It’s the culprit in numerous and sometimes fatal foodborne illness outbreaks. But it’s far from the only bad guy.

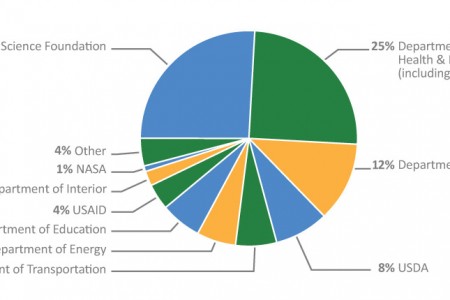

O157 is just one of about 100 Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, or STEC, strains that sicken people and cause 265,000 illnesses annually in the U.S. UNL leads a major project targeting the eight most dangerous E. coli strains throughout the beef production chain. Funded by a $25 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, this project involves 11 universities and other institutions.

“The long-term goal is to reduce the occurrence and public health risks from Shiga toxin-producing E. coli in beef, while preserving an economically viable and sustainable beef industry,” said UNL veterinary scientist Rod Moxley, who leads the project. “This can only be accomplished by a multi-institutional effort that brings together complementary teams of the nation’s experts, whose expertise spans the entire beef chain continuum.”

“We will look at these existing interventions and determine their efficacy against other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli.”

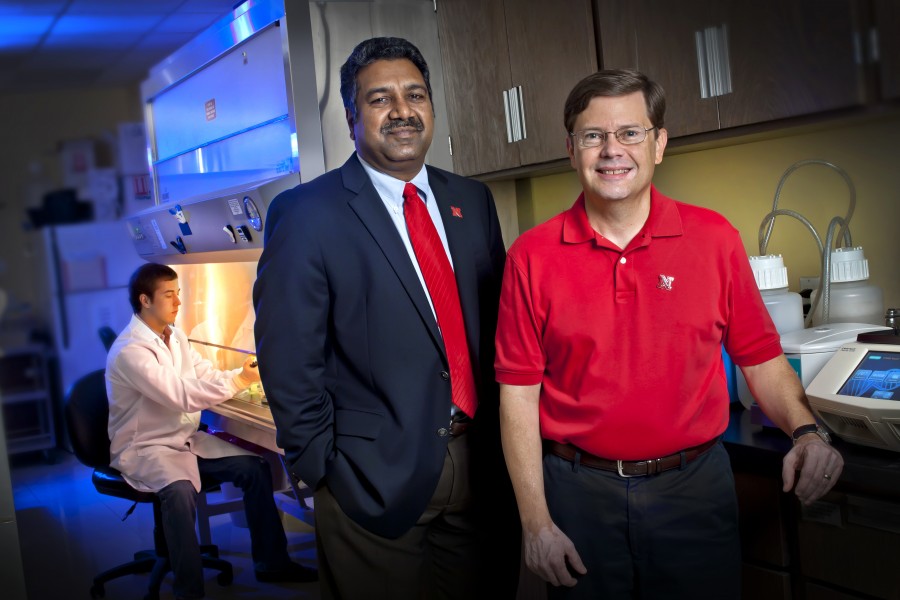

Moxley and UNL food scientist Harshavardhan Thippareddi are on a team focusing on better detecting these dangerous strains. Both are veterans in the fight against O157, and this project builds on years of research at UNL and nationwide that produced interventions to reduce the incidence of O157.

“We will look at these existing interventions and determine their efficacy against other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli and also to develop other interventions as needed,” Thippareddi said.

E. coli testing methods need to be improved because the organism spreads inconsistently in animals.

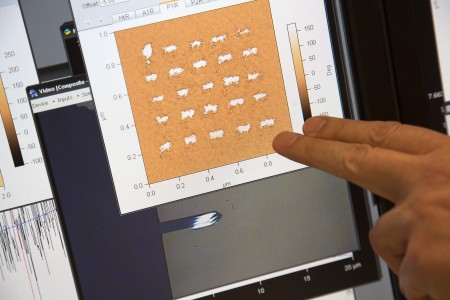

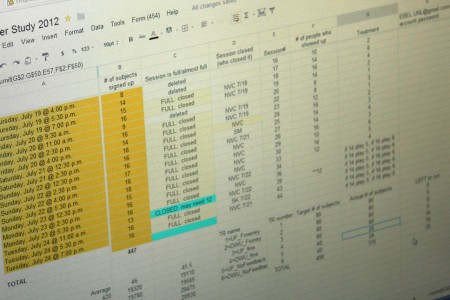

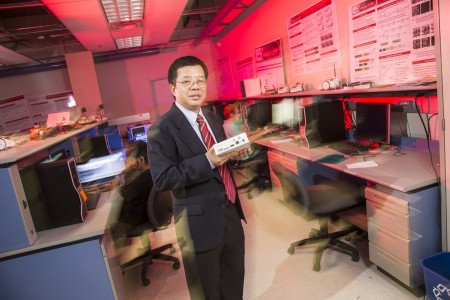

A key goal is developing a portable detection method that could be used in packing plants, Moxley said. Tests need to spot the eight STECs in areas such as cattle feces, meat, water, soil, feed, carcasses and hides.

Project partners will play important roles, Moxley said. For example, Kansas State University, a major contributor, has a state-of-the-art biosecurity research facility where scientists can infect animals and study them.

New vaccines for cattle also are a potential outcome.

2011-2012 Research Report

2011-2012 Research Report