Countering killer heat in cities

Extreme heat is the leading natural disaster-related killer in the United States. Especially acute in urban areas, it is expected to worsen as climate change intensifies.

A Nebraska researcher is working to better understand the phenomenon and find ways for policymakers and citizens to counter it.

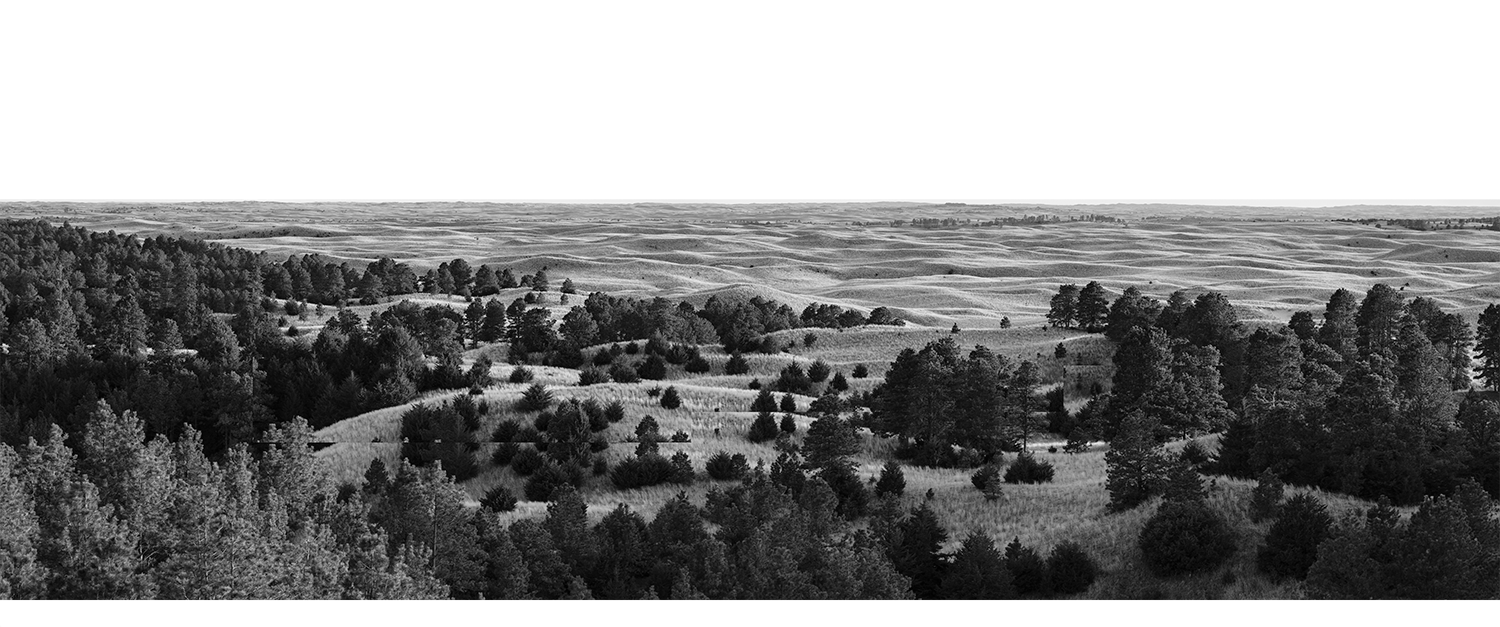

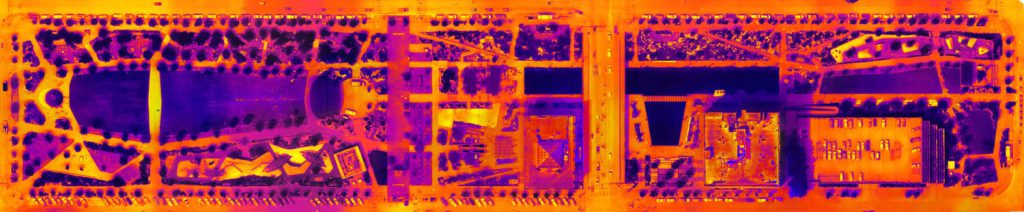

Salvador Lindquist, assistant professor of landscape architecture, leads a research team focused on Omaha, where the historically discriminatory practice of “redlining” has left the city among the 50 most segregated cities in America. An ongoing study of extreme heat in Nebraska’s largest city has found a 10-degree difference in average temperatures between formerly redlined neighborhoods and others.

Extreme heat is especially pronounced in urban areas, where buildings, roads and other infrastructure absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat.

Omaha is in the midst of developing by June 2024 a climate action plan that Mayor Jean Stothert says will include tackling extreme heat. Lindquist’s team aims to provide research to help inform that plan in a partnership that includes the city’s planning department, the University of Nebraska Medical Center and UNL’s College of Architecture.

The team’s approach includes an attempt to gather more granular heat data. Traditionally, researchers have used remote sensing equipment whose data is limited and often overlooks the reality of living amid extreme heat. Lindquist’s team is using more precise, on-the-ground equipment to give policymakers more useful information.

Lindquist said there’s no “one-size-fits-all approach,” but he aims to develop “a toolkit for landscape planners and policymakers to make better-informed decisions in designing more just and equitable cities.”

Lindquist said researchers expect to develop both mitigation and adaptation approaches. Mitigation might include developing more green spaces and planting more trees in the city. For adaptation, he added, plans may encourage Omaha, a very “car-centric city,” to more actively embrace public transit and perhaps build comfort and cooling centers.

He acknowledged that getting people to adapt is much more challenging than mitigation but “those two things need to work in conjunction.”

+ Additional content for Countering killer heat in cities

CNN Business: ‘We’re cooking our cities’: These drones map 150-degree temperatures in urban areas