Expanding rural access to juvenile justice attorneys

New attorneys often struggle to learn the ropes. But the early years of practicing in juvenile law – a field blending criminal and civil law with complex social and family dynamics – are particularly challenging.

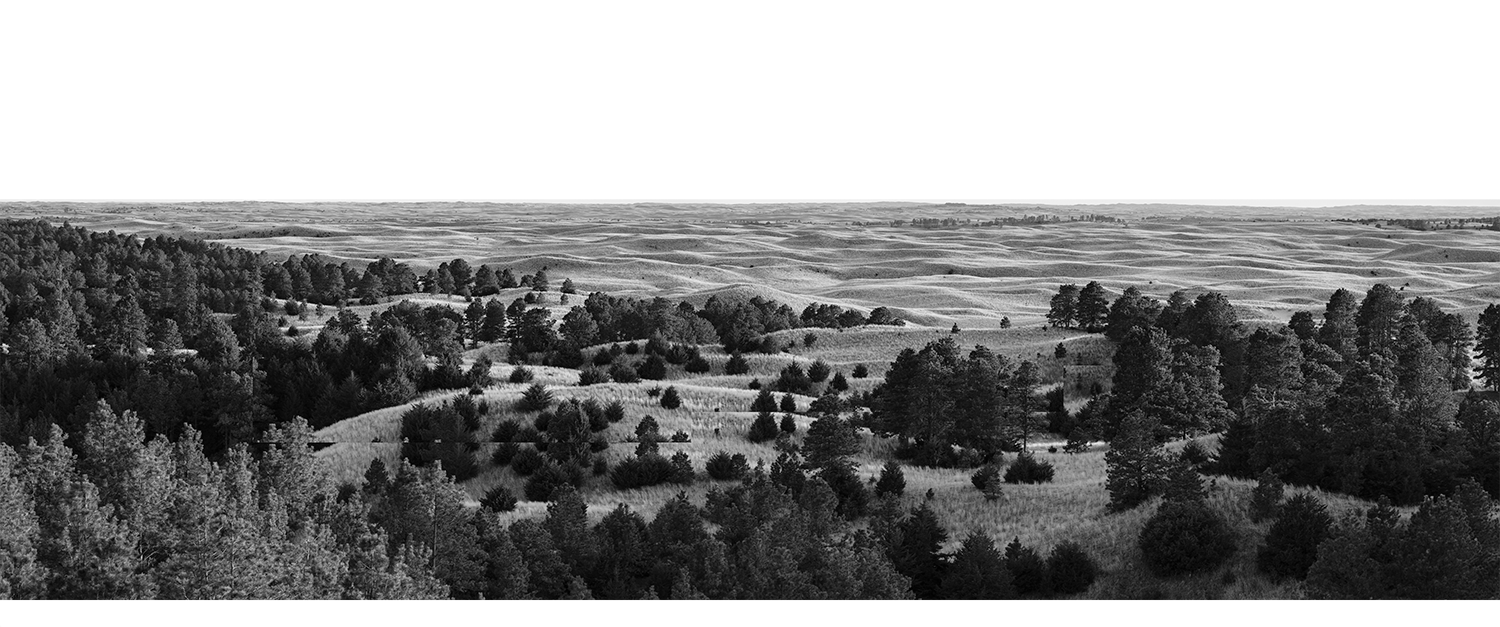

And working in a rural area, with fewer local colleagues and resources, compounds these difficulties.

“When you’re rural, you don’t know where to look or who to talk to,” said Audrey Kingston, a general practice attorney in North Platte, Nebraska.

Nebraska’s College of Law and its Center on Children, Families and the Law launched the Children’s Justice Attorney Education Program in 2021 to fill these gaps. The program equips rural attorneys to provide high-quality representation through a broad range of tools. The ultimate goal is to improve outcomes for vulnerable children and families in these communities by retaining skilled attorneys.

The Aviv Foundation and a private foundation fund the program.

Fellows receive extensive training on state and federal child welfare and juvenile justice laws. The program includes education on social and psychological factors.

“Many of the skills to be high-quality counsel in juvenile court go beyond what you’re typically taught in law school, including trauma, substance abuse, human trafficking and domestic abuse,” said program director Michelle Paxton, who also leads the university’s Children’s Justice Clinic.

Participants can consult on cases with an array of child welfare and juvenile justice experts, including psychologists, attorneys, social workers and mental health practitioners. They also learn strategies for coping with the emotional stress of practicing juvenile law.

Perhaps most importantly, the program connects rural attorneys from across the state. Kingston, a member of the program’s first 12-member cohort, said these relationships are invaluable. Leveraging her peers’ knowledge, she’s learned about different approaches to filing cases and resources available in different communities.

“Personally and professionally, that networking factor was huge,” she said. “It’s great being able to email someone else to bounce ideas off each other, figure out how to juggle a practice and emotionally deal with the work.”

Paxton said the program, now in its second year, could serve as a model for other states with a rural attorney shortage.

+ Additional content for Expanding rural access to juvenile justice attorneys

Nebraska Today: Grant will expand access to attorneys in rural areas

PR Newswire: Inaugural Springboard Prize for Child Welfare Grants $800,000 to Awardees