Nebraska interdisciplinary scholar Peter Revesz has a unique skill set, one that helped him solve a mystery that had puzzled experts for nearly two centuries.

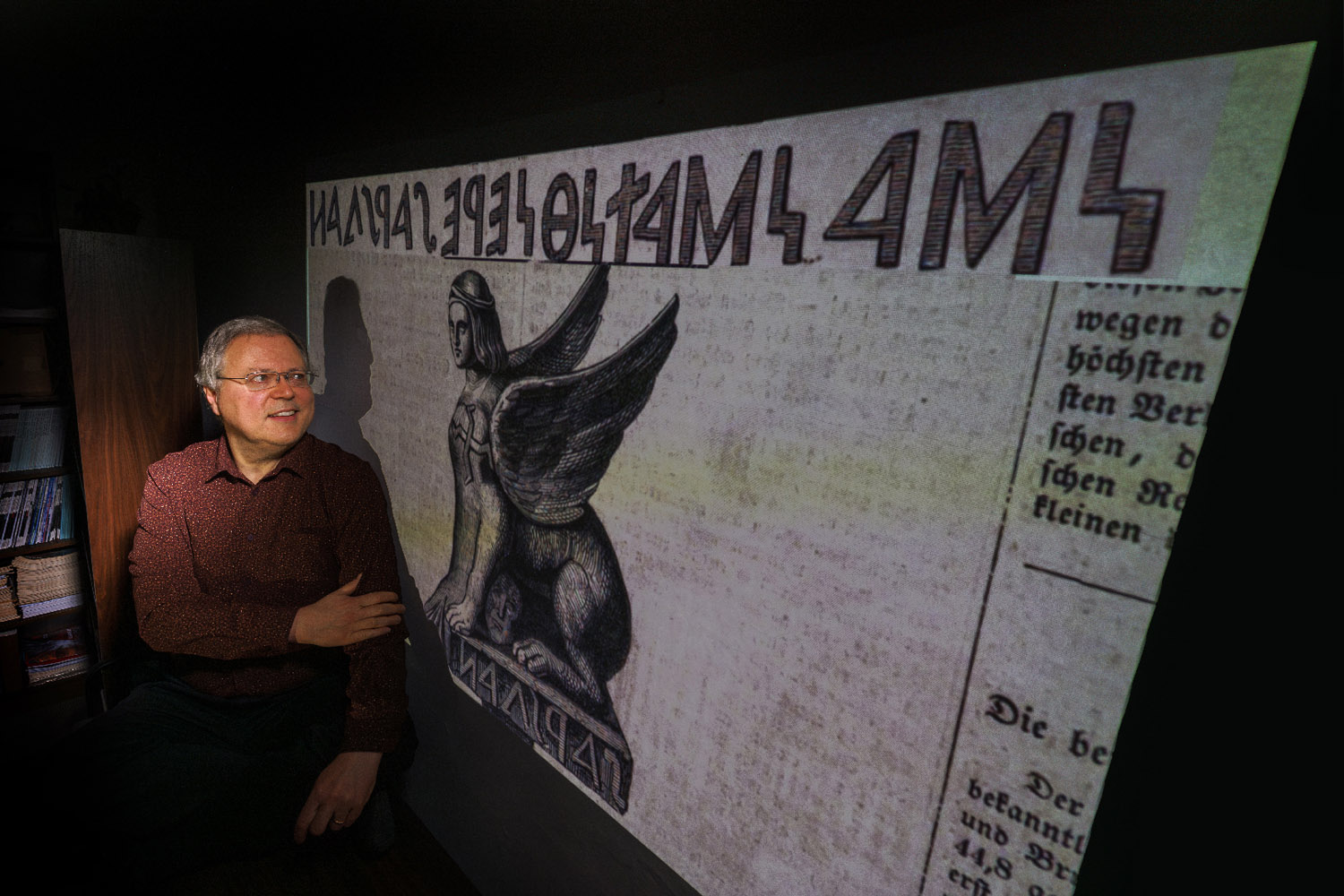

Drawing on an interest in ancient Greece and a Hungarian childhood, Revesz, a computational linguist, deciphered a short poem at the base of an ancient bronze sphinx. His discovery, covered in over 50 news articles worldwide, helps scholars understand cultural life and languages during the Roman era.

The translated poem reads: “Lo, behold, worship! Here is the holy lion!”

Just 20 characters long, the inscription uses archaic Greek letters to convey a proto-Hungarian language.

Dating to the third century, the statue was discovered in the early 19th century in the archeological site of Potaissa in modern-day Romania. Potaissa began as a Roman army outpost following the conquest of Dacia and developed into a town. The sphinx, in the form of a winged lion, was stolen around 1848. Though it was never recovered, a detailed drawing remains.

Revesz’s interest in Greek language, which he explored as a 2008 Fulbright scholar in Athens, Greece, led him to use computer science techniques to study how ancient languages evolved. This knowledge and his previous successes deciphering inscriptions helped Revesz decode the sphinx.

The inscription is written right to left with some characters mirroring images, an archaic Greek writing style. Critically, Revesz recognized the Greek letters were used phonetically to render words in a proto-Hungarian language without its own alphabet.

Revesz immigrated to the U.S. from Hungary as a child, retaining his native language, although he long thought it wasn’t useful.

“In the end, I’m glad I know the language of my parents,” he said, with a laugh.

Revesz’s discovery improves scholars’ understanding of the diverse groups that settled the area following Roman colonization, including early Hungarian speakers.

It also sheds light on a minority religion. Sphinx worship originated in Egypt and was common in ancient Greece but wasn’t part of Roman mythology. The inscription is a metric poem and may have been intoned during religious celebrations.

“It enhances our understanding of how people lived and interacted with each other. It’s fascinating,” said Revesz, professor of computing.

The study was published in Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry.

Additional content

- News release: Revesz decodes ancient sphinx’s mysterious message

- Journal abstract

- Miami Herald article

- Yahoo! News article

Peter Revesz