Mapping Genome Promises to Enhance Ancient Grain

Humanity has finally gotten to know one of its oldest, most water-efficient crops on a genetic level.

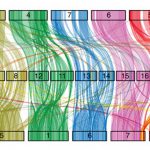

Nebraska’s James Schnable and an international team have sequenced and mapped proso millet’s genome. This information is essential to increasing the drought-resistant crop’s yields in Nebraska’s Panhandle and semiarid regions worldwide, where population growth foreshadows food shortages.

Because millets can grow in poor soils and need less water than other cereal crops, several have become popular among subsistence farmers in ever-hotter, drier swaths of Africa and Asia. But millet’s relatively low yields and traits that make harvesting difficult limit its viability as a food, feed or fuel staple.

James Schnable

James Schnable

To inform future breeding efforts, Schnable and colleagues sequenced more than 90 percent of the genetic code in proso millet, a species grown mostly in the American Great Plains, northern China and parts of Europe.

The ability to pinpoint the location, composition and size of proso’s genes should help researchers rapidly improve traits and tailor varieties to climates around the world, said Schnable, associate professor of agronomy and horticulture.

“This will have a huge potential impact on the rural economy of the region.”

Dipak Santra

“There’s potential to grow it on a much larger scale and take a significant bite out of the amount of additional grain we need to meet the demand for feed and food and ethanol,” he said.

Nebraska’s farmers will benefit from that genome-guided work, said Dipak Santra, associate professor of agronomy and horticulture at the university’s Panhandle Research and Extension Center.

Researchers reported their findings in Nature Communications. Schnable’s collaborators were from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Iowa State University, Henan University, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University, Purdue University, Dryland Genetics LLC and Data2Bio LLC.

“This will have a huge potential impact on the rural economy of the region,” said Santra, the lone public-sector proso millet breeder in the Western Hemisphere. “Proso millet’s direct value to (the semiarid High Plains) is $45 million per year, but considering its benefits to the dryland production systems, its total value to the region’s economy could be closer to a billion dollars.”

Additional content

Nebraska news release: Sequenced genome of ancient crop could raise yields

2018 - 2019 Report

2018 - 2019 Report

2018 - 2019 Report

2018 - 2019 Report